Story by Blake Sandlin

Interim Editor-in-Chief

bsandlin1@murraystate.edu

There are two sides to Ja Morant’s turbulent, yet providential story.

There’s the side the world is seeing – the acrobatic highlight dunks, the outlandish ball control and breathtaking court vision, the breakneck speed and athleticism. The side of a guy who’s averaging 24.3 ppg and 10.2 apg, and is on pace to become the first Division I player ever to average 20 points and 10 assists per game for an entire season.

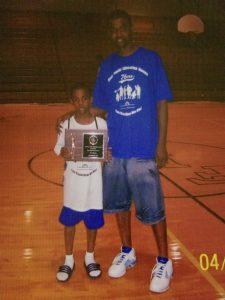

Then, there’s the side few have seen, but many are now learning about. The kid who spent countless hours training with his father, Tee, on their backyard basketball court, jumping on tractor tires and perfecting his ball handling. The boy who would sometimes sneak in the car with his dad on school days to watch his adult rec-league games.

And of course, the same boy who, despite his relentless work ethic and unbelievable high school stat lines, had to watch helplessly as his friends and teammates received the high-major college scholarships and notoriety he desired.

What to some onlookers looks like a meteoric rise from nothing, Morant and the tight-knit family who raised him always knew there was something special about that wiry kid from Dalzell, South Carolina, even if nobody else did.

Dalzell, a quaint, rural town of 2,260 on the outskirts of Sumter, South Carolina, is largely made up of miles of farmland. There’s few restaurants and no grocery stores, having just a couple of Dollar General stores scattered around amongst some gas stations.

The Morant family’s reputation as athletes didn’t begin with Ja. His grandfather and his uncle were drafted into the MLB, while Ja’s mother, Jamie, was a two-sport athlete with softball and basketball. His father, Tee, played DII basketball at Claflin University and came just short of fulfilling his NBA dreams.

“The DNA was incredible,” Tee said. “I will claim our DNA is incredible. Did I say our DNA is incredible? He’s got an incredible genetic line as far as athletics. But once he took the basketball, it was all basketball, all workouts, all everything.”

DNA aside, Jamie knew long before now that she had something special in Ja.

“My wife will tell you she knew Ja was going to be great when he was in her belly,” Tee said. “She actually said that. I guess that’s that woman intuition. But, at the same time, you second-guessing her now?”

But, Ja’s success can’t be solely attributed to his unique pedigree. It started with work ethic – one that was fostered within him from as early as 2 years old.

“He was probably like 2, and we had a sectional,” Tee said. “Anytime he did something wrong, I put an in-house [basketball] goal that we had behind the sectional, and then threw two basketballs back there and a bottle of milk. So either he was going to shoot the basketballs, or drink the milk and go to sleep.”

Despite his basketball skills not being fully developed, he made the biggest leaps during his infancy. The bulldogged resiliency and fearlessness that’s become a trademark of Ja’s on the basketball court was actually forged on a different stage.

As young as 4 years old, Ja would dress up like Michael Jackson and perform in front of big crowds at cookouts, in front of friends or just in his living room.

“Ja was full-blown Michael Jackson with the jacket, the hat, doing all of it,” Carol Morant, Ja’s aunt, said. “We would call him out, and he would get in full performance and have everybody watch his performances. So he’s been performing for a long time in different capacities. He’s known how to entertain from a young age.”

Tee would often pressure him to perform in front of the crowds intentionally, in order for him to build up his confidence. Ja never folded under pressure and always delivered a show.

“If you can perform there under a controlled environment, well, when the bright lights came on, you wasn’t nervous,” Tee said.

Ja believes the moonwalking days helped prepare him for the pressures of performing fearlessly in front of thousands.

“I don’t be nervous,” Ja said. “So, I feel like that helped. They used to make me dance sometimes, but I got used to it. I already knew what he was going to say and stuff, so I’d just do it on my own.”

The precocious child soon translated his confidence to the hardwood. Because there were no leagues available for a 6-year-old at that time, Ja played up in a 7-to-9-year-old league. What he lacked in stature, he made up for in surprisingly accurate passing ability and ball handling.

“A 6-year-old playing against 9-year-olds was still scoring,” Tee said. “He’s scoring buckets and making passes that 9 year olds don’t see yet, like I wasn’t expecting this ball.”

A family friend of the Morants, April Rogers, watched Ja grow up. He and his friends would sometimes spend days at her house dancing and having fun, or chowing down on Rogers’ peach cobbler, one of his favorite dishes.

“At that age we were wondering why he was even playing with those kids because he could dribble at that time and he could shoot at that time,” Rogers said. “We were so amazed, and we watched him grow over the years.”

And grow he did. While he was still one of the smallest players on the court, the confidence and self-esteem he cultivated in the backyard carried them through and no one had to look hard to see it.

At 9 years old, playing for the South Carolina Ravens, Ja was nailing three after three in a defender’s face. When he hit a shot, he would flash WWE wrestler John Cena’s patented “You Can’t See Me” hand sign arrogantly, much to his father’s displeasure. Tee screamed for Ja to stop showboating during that game, where Tee said he would ultimately finish with around 25 points.

At halftime, Tee ran into an older man named Wilbur Singleton, who played for Wake Forest years before.

“Wilbur walked over to me at halftime and said, ‘Tee Morant, do you see how Ja is doing them?’” Tee said. “I said, ‘Yeah, he’s just showing off too much.’ And Wilbur said, ‘Remember this: the boy is 9 years old playing against 10 and 11-year-olds, and he’s got the confidence to do what he’s doing. If you don’t believe nothing else I say or listen to anything else I say, listen to this: let him go. He’ll be fine, because he’ll have the confidence to do whatever he wants during a game. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh.’”

Even after games, Ja’s perfectionist nature was on display. No matter how many assists, points or wins he raked in, he had an insatiable desire to keep improving. Tee and other coaches would make Ja and his teammates critique and grade their individual games on the drive home in order to improve their basketball IQ’s.

Ja would oftentimes judge himself harshly even when he played exceptionally, leading the other players to adjust their own grades accordingly.

“There’s a lot of times we’d get out the van I’d be like, ‘Why the hell you give yourself a five? You had like three turnovers, you had like 25 points and eight assists,’” Tee said. “But that was just me being real. I never gave him the seal of approval. I always told him he was overrated and all that. My wife would be like, ‘Why you always tell him that?’ I’d be like, ‘Because I got to keep him hungry.’ And now, people asking me, ‘Why’s your boy so hungry?’ And I say, ‘Because I haven’t been feeding him [crap].’”

Ja’s IQ was even manifested in the virtual world. His uncle, Phil Morant, used to babysit Ja and his cousins while his father was working. They spent their time playing the popular basketball video game “NBA 2K.” Even as early as 9, Phil said he could spot Ja’s unique intelligence for the game by the way he utilized the players according to their skillsets.

“He started following Russell Westbrook,” Phil said. “If you remember, Russell Westbrook would always dribble real fast to the free throw line and pull up. So he’s doing this, and I’m checking out his IQ. And I’m telling Tee, ‘He is using everybody the way they’re supposed to be used.’ I’m trying to figure out who the hell I can funnel the ball to to make him lose this game, then he started beating me and it was over with from there. I don’t even play him no more.”

Although his IQ kept inflating, his small stature remained constant. Ja was around 5 feet, 5 inches through middle school. Tee began to worry that his son may never have a future in basketball.

“I was nervous,” Tee said. “I was like, ‘I’m gonna have to teach this boy a whole lot of step-backs so he can get a shot off.’”

Fortunately for Ja, he started to hit a growth spurt after middle school. By the time he reached high school, he had skyrocketed to about 5 feet, 10 inches, and by his junior year he stood six foot. As he began to grow, his natural athleticism started to show. Tee kept his son out of AAU for most of the summer of his ninth grade year in order to train.

To develop his speed and athleticism, Ja trained with resistance parachutes, drilled defensive slides, ran hills and elevated his vertical leap by jumping on tractor tires. As his vertical increased, Tee would increase the jumps on the tractor tires to maximize the drill’s effectiveness.

The additional training paid dividends. Ja performed his first in-game dunk the summer of his 9th-grade year. That’s when Tee realized his son was cut from a different cloth.

And so began the ascent of Ja Morant. His work in the backyard with his dad accelerated as he advanced through his career at Crestwood High School in Sumter, South Carolina. Yet as his skillset advanced, his humility stayed the same.

When Dwyane Edwards, Ja’s high school coach at Crestwood, considered bringing him up for varsity when Ja was a sophomore, Ja told his coach he needed another year to prove himself with the junior varsity team.

“He knew where he was,” Rogers said. “He knew where his level was. If he was somebody that was real cocky and didn’t care about the team winning, he would’ve just been thinking about himself and he would’ve jumped at that opportunity. He would’ve made sure he got himself playing time.”

That extra year of development at a lower level afforded Ja the opportunity to improve all facets of his game, and by the time he reached the varsity level, he did just that. Ja averaged an astonishing 27 points, eight assists and eight rebounds in two consecutive seasons at Crestwood, but if you asked his coach, it was the intangibles that made him special.

“If you put four other guys around him, he’s gonna make them better,” Edwards said. “I always tell them all the time, that’s why I always liked Magic [Johnson], because Magic always got the most out of his guys, and that’s Ja. To be honest, you could have an average player, but playing on a team with Ja Morant, he could make it seem like you’re a pretty good player because he’s going to get them involved.”

Throughout high school, Edwards said Ja’s game was one step ahead of other players. His extraordinary vision and basketball IQ allowed him to make passes no one saw coming, not even his own teammates.

But, it wasn’t how he did it; it was the way he did it. Crestwood’s offense was very similar to the Racers’ now – defined by run-and-gun transition play and a lot of freedom of movement for players.

“I had an offense, but if you’ve got Ja Morant and you got the floor spacing or on a break or whatever, he’s gonna make the best decision when it comes down to trying to get that basket,” Edwards said. “He had that freedom with me.”

Even the untrained eye of the casual fan noticed Ja’s ability to lead an offense almost single handedly.

“You could see it all on the floor,” Rogers said. “He was a general on the floor at all times, and I remember him even calling timeouts at times because I sometimes sat behind the bench. I remember him calling timeouts at times and telling the coaches, ‘They’re doing so and so and so and so, so we need to do so and so and so and so.’ That’s the way it went. They went back out there and did it.”

Edwards knows a thing or two about talent evaluation. As an assistant coach at Crestwood High, he coached a team consisting of Ja’s father Tee, as well as NBA great Ray Allen. He said Ja’s tireless work ethic in high school directly correlated to his success on the court.

“Ja would practice with me, then he’d go home and practice with his daddy after practice,” Edwards said. “You couldn’t open the gym enough for Ja Morant. You couldn’t open it enough. ‘Coach, can you open the gym this Sunday? Can you ask coach Brown?’ We’d finish up, then he’d go to the backyard with his daddy and shoot some more.”

Anyone you talk to around Dalzell raves about that same work ethic Edwards described. However, even as Ja terrorized teams in South Carolina his senior year, he oddly didn’t attract the same power-five offers that some of his friends and AAU teammates did.

Ja watched as players like Zion Williamson and Devontae Shuler – two South Carolina players who played on the same AAU team as Ja the summer of his freshman year – raked in national hype and a plethora of DI offers, while Ja – yes, the same Ja that averaged 27, eight and eight – had just two offers from South Carolina State and Maryland Eastern-Shore following his junior campaign.

The teenage Morant was baffled, and so were the family and friends around him.

“We was stumped pretty much,” Tee said. “It felt like our hands was tied, and somebody was like beating the hell out of our child. He’s putting everything out there. He’s showing the work. He’s showing how good he is. But at the same time, what are [scouts] seeing that we’re not seeing?”

Though he was distraught, he didn’t show it. He continued to work in silence, praying he would ultimately see the fruits of his labor. Through it all, though, it was his relationship with his mother and father that helped him endure. The Morants had a mantra, “These four walls,” meaning anything that didn’t affect the bond between the tight-knit family was none of their concern.

Tee did his best to console his son. He constantly reminded him that “cream would always rise to the top.” Jamie was quick to remind him he was “beneath no one,” a phrase Morant has tattooed on his left arm.

While Tee and Jamie were working fervently to encourage their son, it was the spiritual support of Ja’s grandmother, Linda Smalley, that gave him the boost he needed to endure the trials that plagued his high school path.

Affectionately known as “Mama Lin” around the Morant household, Ja’s grandmother never showed him how to improve his jumper, never trained with him on the basketball court and never complained about his play or concerned herself with wins and losses.

What she did do, however, was give Ja the encouragement to keep going through the good times and the bad – and for a young, confused and troubled Ja Morant, that support was paramount. She didn’t do it for Ja Morant, the athlete. She did it for Ja Morant, the person.

“I don’t care how the performance was or if it was sports, Mama Lin had encouraging words always,” Tee said. “That’s the crazy thing, because I work at a barbershop and I tell a lot of people that there ain’t too many grandmas out there these days that are willing to drop everything for their grandchild… Mama Lin was never pushing the envelope as far as him being an NBA player or Hall of Famer or anything; Mama Lin was pushing for him to follow God’s plan.”

Smalley, who lives in Appling, Georgia, would sometimes get texts from Ja asking for prayer or a simple scripture to get him through his day. Smalley said Ja told her he felt like God had big plans for him, even though his current struggles weren’t reflecting that.

“There was times when I used to go back to Georgia and stuff, she used to take me and my cousins to church,” Ja said. “I know everytime she could just feel when something was up or anything, and she would just tell my mom to give me a prayer or scripture to read. I just got so comfortable with it that times when I felt like the Devil is trying to attack me or anything, I’ll just go to her.”

Smalley knew her grandson’s struggles wouldn’t last forever.

“With God’s plan, nobody can stop it,” Smalley said. “It can’t even stop itself.”

And it didn’t. Even when the high-major offers never came, Ja stuck to God’s plan. Anyone who’s paid an inkling of attention to college basketball this season knows how that plan’s played out.

Former Murray State basketball assistant James Kane serendipitously stumbled upon Ja playing 3-on-3 in the side room at an AAU tournament while he was searching for a snack. Kane was actually scouting current Racer freshman Tevin Brown. Ja wasn’t even listed on the camp’s official roster. Kane immediately called Murray State Head Coach Matt McMahon, and the Racer coaching staff made Ja their top priority.

From that moment on, Ja finally received the one thing he’d been craving: loyalty. He took a visit to Murray State on Sept. 1, 2016, and committed to the school that day. He was scheduled to take his official visit to the University of South Carolina weeks later, but it was the love and commitment Murray State showed him that ultimately sold Ja on the school.

“Ja says this is where he want to be at, and he graded it out and was like, ‘This is why: They never lied to us,’” Tee said.

A lot has changed since then.

Ja is currently leading the country in assists at 10.2 per game, and just recently broke the OVC single-season assist record. He’s added a handful of emphatic highlight-reel dunks to his resume and is the toast of SportsCenter most nights following games. He’s busted into the national conversation, and is currently projected by several mock drafts to be drafted second in the 2019 NBA Draft.

But some things never change.

Ja still texts “Mama Lin” to ask for prayer and scripture on occasion and FaceTimes his parents constantly. He still visits April Rogers’ house when he has a hankering for her coveted peach cobbler. He’s still infatuated by Russell Westbrook skill, and will soon go from controlling him in video games to facing off toe-to-toe.

He still hasn’t forgotten about Dalzell, and his old high school coach hopes Dalzell doesn’t forget about him anytime soon.

“I want him to just show kids, and it doesn’t have to be basketball, that if you’ve got goals or you’ve got a dream you’re working towards that you can make it,” Edwards said. “That’s what Ja Morant owes Crestwood. Just be there and show them that he made it.”

Even as national acclaim rains down on him and he’s met with endless lines of fans yearning for photos and autographs after games, Ja is acutely aware that this isn’t the end goal. There’s a reason his father kept him hungry, and it’s only a matter of time before there’s a full-course meal waiting.

“Since I’ve been playing, I don’t think I’ve ever heard my dad say, ‘Boy, you a great player,’” Morant said. “It’s always just something with him. He always just tells me about the bad stuff. As of now, with all the attention I’m getting and stuff, and the people calling me overrated, it’s really nothing new that I haven’t heard from him. It really doesn’t faze me anymore what the fans say. I really think it’s just them poking the bear. That’s when I show how I really play.”

There are two sides to Ja Morant. Each tells its own story, but together they’re emblematic of one complete picture – one depicting a man primed to make it so that he can finally give back to those who helped make him.